India’s Smart Cities Experiment- Technology Without Empowered Cities?

By Nidhi Tambe, Research Assistant, Pune International Centre. PS: -Views expressed in this blog are completely personal.

Successful urban planning is often backed by strong, implementable proposals, integration of new plans with existing schemes & municipal budgets, so that cities operate smoothly, efficiently, and inclusively. This is important because, by 2030, more than 40% of the Indian population is estimated to reside in urban areas, according to reports by NITI Aayog (1) (2) . Given the scale and rate of urbanization, it becomes necessary that Indian policy-makers rethink and reinvent the urban policy and governance frameworks.

The 74th CAA was introduced to provide a comprehensive overhaul of India’s urban governance framework by granting urban local bodies autonomous status and formally recognizing the third tier of government. It granted the ULBs the long-required autonomy on various fronts such as finance, governance, and decision-making. However, despite the constitutional framework for devolution, urban decentralisation remains uneven, resulting in limited fiscal autonomy, parallel institutions, capacity constraints, and fragmented responsibilities. Consequently, all the urban development initiatives in the years that followed the 74th CAA were largely sector-specific and scheme-driven, focusing on individual issues rather than an integrated citywide transformation.

The gap between constitutional intent and urban outcomes created the need for a programme-led intervention. First of such interventions was the JNNURM, which attempted to strengthen cities through infrastructure and institutional reforms. However, it largely remained a top-down investment-driven programme and was inadequate to address the growing complexity of urban challenges, ranging from climate risks and service inefficiencies to citizen engagement and data fragmentation. Addressing such challenges required a fundamentally different governance logic in which it was no longer sufficient to build assets. Cities now need to manage systems as a whole.

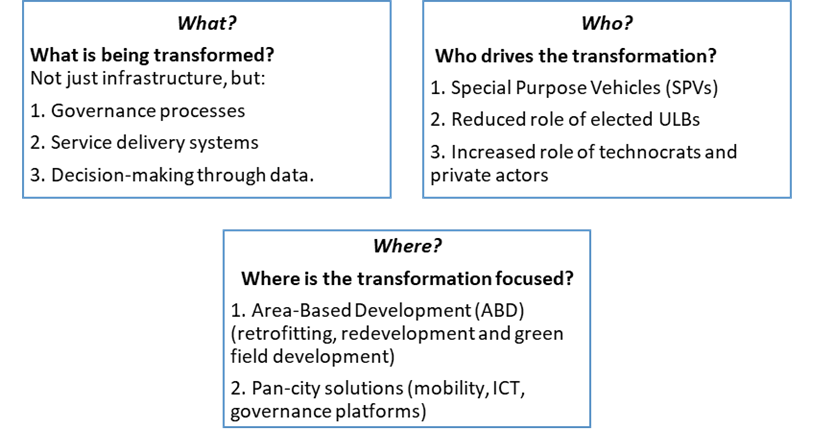

Smart Cities Mission (SCM) emerged from the challenges mentioned above and aimed to build upon the gaps in JNNURM through a more integrated, technology-enabled approach. The figure below captures the essential features of the SCM.This gave rise to the Smart Cities mission, which aimed to build upon the gaps in JNNURM through a more integrated, technology-enabled approach.

Figure 1: Essential Features of SCM

What Made the SCM different?

The SCM stood apart from the past missions by pushing cities to design and implement area-based development plans. The essential idea was to move cities away from the traditional paper-based master plans towards geographically focused interventions that bundled streetscape improvements, public spaces, mobility, and basic services into coherent precinct-level projects.

Financially, the SCM was granted Rs. 50,000 cr. for a period of 5 years (i.e., Rs. 100 crs. per year per city) which was to be matched equally by the states and ULBs. Over and above the direct budgetary support, the Mission proposed to mobilize long-term institutional capital through the NIIF. It was also expected to ensure convergence with other flagship programs like AMRUT, the Swachh Bharat Mission, HRIDAY, and Housing for All. The SCM also had to promote market-based instruments such as public–private partnerships and municipal bonds at the level of ULBs, adhering to financial sustainability through user charges for operation and maintenance.

Furthermore, there was to be on-ground Integrated Command Control Centres which emerged as the Mission’s backbone, integrating data from traffic systems, utility, centres, and over 84,000 CCTV cameras to enable real-time decision-making. The SPVs were formed under the Companies Act 2013, with the aim to speed up the process of execution and professional management. These special institutions bypassed the municipal bodies through a ring-fenced financing mechanism.

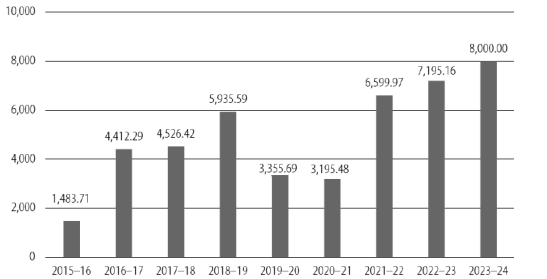

Figure 2: Budgetary Expenditure under SCM in India, 2015-24 (Rs. Crore)

Source: (Hastimal G Sagara)

Key Outcomes

SCM delivered measurable gains, such as adaptive signals that cut traffic delays, smart lighting, digitised grievances boosted response times, and asset mapping enhanced tax revenues. These stemmed from outcome-tied funding, competitive selection, and tech-governance alignment, treating urban issues as integrated systems, unlike prior input-focused schemes. However, despite delivering visible technological and institutional innovations, the SCM exposed deep structural challenges that undermined its transformative potential.

The single most important rationale for the creation of SPVs the current ULBs lacked the capacity to execute and handle complex projects such as the SCM. This naturally led to the establishment of a parallel governing structure that directly bypassed the 74th CAA. Instead of strengthening the municipal institutions, the ULBs were relegated to mere funding and oversight roles while the decision-making shifted to corporatized entities (i.e., the SPVs). The uneasy coexistence of ULBs and SPVs weakened accountability and citizen engagement thereby diluting the constitutional mandate of decentralized urban governance.

“Despite these structural limitations of the SCM mentioned above, a few cities were able to deliver strong outcomes, largely due to the robustness of their municipal finances and administrative systems”.

A few cities under the Smart Cities Mission outperformed others primarily due to their ULBs’ strong pre-existing financial capacity and administrative competence, enabling effective resource mobilization beyond central grants. Indore and Bhopal in Madhya Pradesh exemplify this, the Indore Municipal Corporation issued India’s first municipal green bond (₹244 crore in 2023) for solar projects and monetized 1.26 acres of land for ₹8 crore, while Bhopal generated ₹297 crore from 10.86 acres, alongside both cities successfully issuing municipal bonds in 2018. Surat also ranked high in awards and performance, leveraging Gujarat’s robust ULB finances for high project completion and PPPs. These cases highlight how baseline ULB strength in revenue generation, creditworthiness, and execution capacity amplified SCM outcomes.

The Smart Cities Mission forms a significant legacy that illustrates both the promise and the limitations of the mission approach to urban reform. While technology, finance, and innovation in institutions brought noticeable improvements in some municipalities, the inconsistent results reflect a more profound truth. Sustainable urban change cannot be driven by parallel structures or stand-alone initiatives. Such change must be anchored in competent, accountable, and fiscally empowered municipal governments. It was not a shortage of ideas or financing models that held the mission back, but a more fundamental shortcoming, namely, local institutions that were weak in authority and capability.

The experience with SCM reveals a profound truth: India’s urban destiny will be determined not by smarter projects but by stronger municipal governance.

Thanks for reading! This post is available for free. Please feel free to share it with others.

Beyond The Blueprint is an initiative of the Pune International Centre (PIC) under the Co-Operative Federalism and Multilevel Governance. PIC is an independent and multidimensional policy think tank based in Pune. PIC does not solicit any payments or subscriptions for this blog series.